Hoo

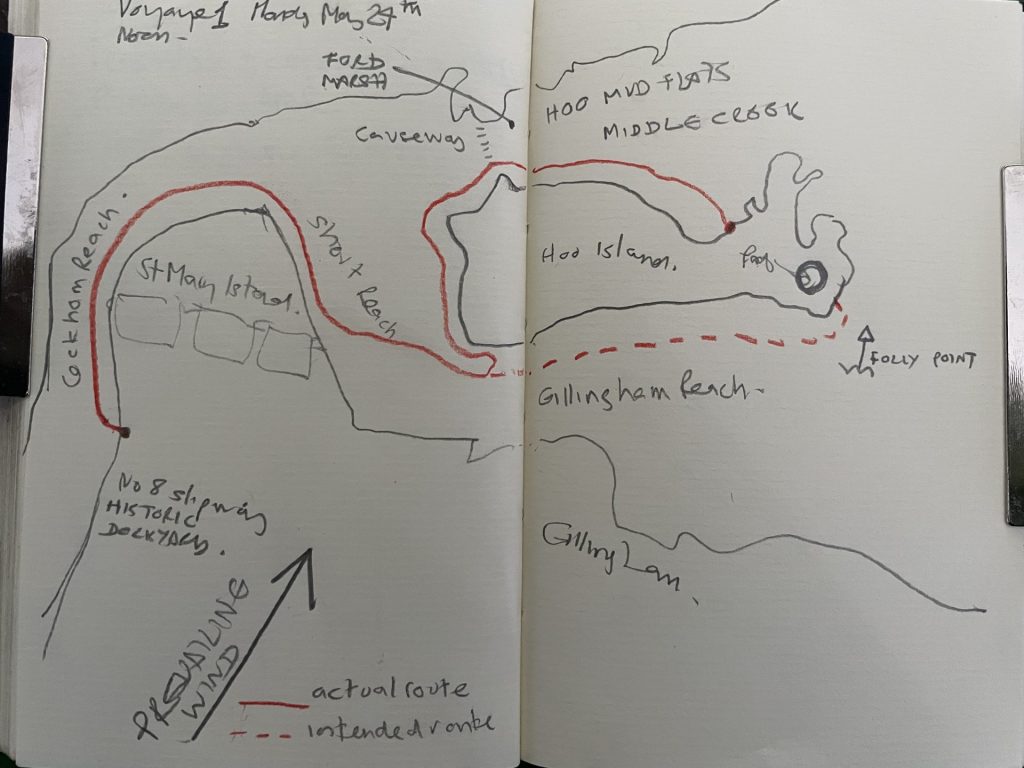

After leaving the Dockyard from No.8 Slip, a gusting south westerly comfortably drove us along, until the river curled south and east toward Gillingham Reach and we were hit broadside on by three foot waves. The Army could easily cope in their seven metre RIBs and 70hp engines, but a 3.1m Magwitch and a 3.5hp outboard, was at its limit. Laden with fuel, water, food, tents, sleeping bags and toilet bucket it was getting uncomfortable and seeking shelter, I turned the boat about at Hoo Ness to skirt the more sheltered northern shore across the shallows of Hoo Flats. We then ran out of fuel and had to paddle like fury to reach land – as the wind and receding tide tried its best to suck us out to Middle Creek.

Whilst the squalls stood off for a while and circled around our camp, we managed to erect our tiny tents and staved off the cold with welcome flasks of hot tea and coffee and Carols’ pre-prepared tuna and cheese sandwiches. It felt as luxurious as tea at the Ritz.

Sharp shards of glass (not what you need with an inflatable) on the foreshore, did not feel entirely welcoming and we found most everything growing ashore was well provided for with plentiful prickles and thorns, as we walked over the island to visit my old friend from the 1990s – Hoo Fort.

Its defensive ditch was surrounded by a thicket of brambles, hawthorn, nettles, thistles and even spiky new sprouts of primitive teasels that did their best to bar our entry. I’m sure there were other less ‘well armed’ plants there, but my lacerated legs (I’d foolishly worn shorts) definitely coloured initial impressions. After getting through this terrible tangle, knee deep fetid water around the fort entrance (guarded by hundreds of mosquitoes) was about ten unpleasant steps too far. We looked longingly through two huge partly open steel clad doors and reluctantly decided this complete world in little would save for another time.

Instead we went to a broken backed wreck on the eastern shore, where salty winds and briny water were transforming a once staunch steel hull into frail layers of iron oxide, before crunching our way down across a carpet of shells and shingle to Folly Point; its tall steel beacon a blanket of mussels below the waterline and the mussels themselves encrusted with barnacles and all wrapped around with fronds of murky brown bladderwrack. Life was clinging on.